(This is a travelogue I wrote for the paper that pays me to do such stuff — yes my life is that awesome, sometimes! — and I am rather proud of it. Also, Jodhpur is a fun place to visit, especially at this time of the year. Another reason you might want to pack up your bags and head for the edge of the Thar is the Rajasthan International Folk Festival, which promises a rather intriguing cocktail of rustic tunes, camels, forts and food for the nomad soul! See you there, perhaps!)

A view of Mehrangarh Fort from Pal Haveli’s terrace. Go to the Indica restaurant for its view, the cool desert breeze at night and cheap liquor. Photo: Akash Gupta

In a tiny ‘Bishnoi’ (Vaishnav, as per the Hindu caste system) village called Salawas near Jodhpur, an old man, browned and lined by a lifetime of physical labour, shows us around his humble abode – mud-caked houses, thatched roofs with goats and cows tethered, with a couple of peacocks frolicking close by – and treats us to some home-made afeem (opium) and chai.

“Salman Khan shot his infamous black bucks in our village only,” he states pompously, as he unwraps his stash with a flourish. Scraping off bits of the dry stuff, he directs us to eat it and says, “Ab hum aapka apne ghar mein swagat karte hain.”

Singh then proudly shows us his afeem-making machine, a fascinating contraption carved out of wood, with a crusher, two cones for accumulating the juice of poppies and a little serpent idol. He explains that afeem is not so much an addiction as a way of life. “No marriage is sanctioned unless the father of the bride gives his new in-laws some of this. We celebrate, commemorate and cure with the help of this flower. Of course, we cannot grow it here nor have we ever thought of marketing it,” he laughs, his white whiskers, which could be the envy of any royal heir, twitching with mirth at the tourist’s surprise.

There is a practiced aura around all of Charan Singh’s movements. We are instructed to give the man a little token of appreciation. Not that one minds, especially since the man has given us a peek into a hitherto unknown world. We are then driven on to a potter’s and a weaver’s houses – at both places we repeat the routine. Clearly, the burgeoning trade of tourism in Jodhpur has infiltrated the suburbs too, in spirit as well as in economic returns.

This delightful little ‘trip’ is unexpected as our train Mandore Express pulls up earlier that morning into the railway station, disgorging us at an unearthly 5 am. We’ve only planned a romp in the lap of old-style affluence, basking in the reflected light of this warrior clan’s heritage, even as we sample some of that famed Marwari hospitality. Clearly, we are to get much more than we’d bargained for.

Jodhpur was founded by a king called Rao Jodha in 1459, with the nearby town Mandore functioning as capital initially. The Rathores, a clan of Rajputs to which Jodha belonged, ruled the Marwar region for centuries till it finally became a fief under Mughal rule and then a princely state under British rule.

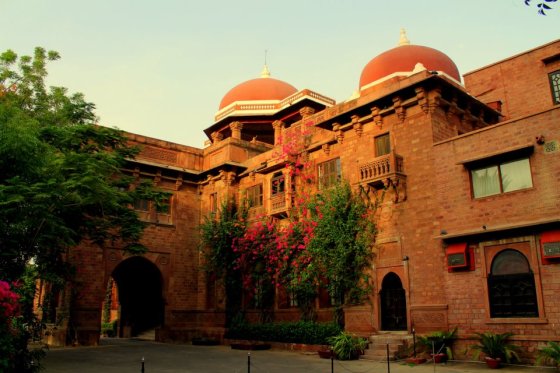

We headed to Ranbanka Palace, a beautiful heritage hotel, situated a bit away from the main city’s bustle. At dawn, the place looked like an oasis of greenery bordered by sandstone in the middle of a rambling desert. The hotel used to be the residence of Prince Ajit Singh, Maharaja Jodha Singh’s (founder of the town) younger brother. Much of the opulence of earlier centuries have been retained and added upon – badges of honour in the form of stuffed deer heads, tiger skin rugs, photographs of previous kings and residents standing over hunted conquests find pride of place everywhere.

The present generation has a different sport to excel at – the bar exhibits Rajkumar Karan Singh’s (the current owner and also a cousin of designer Raghavendra Rathore) laurels at Polo. In fact, we’re informed, the palace hosts a tournament during the winters. We take all this in – the pink walls adorned with bougainvillea creepers, colourful frescoes for windows, rangolis on the floor combined with Jacuzzis, swimming pools, spas and wi-fi connectivity — and realise that the distance between old and new money is easily bridged.

Umaid Bhawan, an important spot of historical importance in the city, is another example of this phenomenon. Commissioned by Maharaja Umaid Singh in 1924, the palace took 20 years to build. Situated on a hillock, it glows a magnificent golden, the sandstone is intricately carved in the style in Rajputana style, and is surrounded by well-tended gardens. While a section of the palace is still the residence of the current king, Maharaja Gaj Singh II, the rest is a museum showcasing royal paraphernalia – jewellery, furniture, armoury, attire and an impressive array of vintage cars, including Bentleys, Cadillacs and even Humbers.

Quite uniquely, the main foyer houses LED displays that pay special tribute to the Edwardian architect of the palace, Sir Henry Vaughan Lanchester, and to interior designer Stefan Norblin, who can be credited for some stunning but slightly out-of-context Biblical murals to be found on the palace’s ceilings. A new gated colony adjoining the palace premises is the most intriguing sight before us. Umaid Heritage Estate is to be a high-end residential area for the industrialists and the super-rich, most famously Mankichand Panwala. Kumar finds this capitalist desire to be part of royalty quite awesome; in some way, this new development makes him feel part of it all.

Kumar tells us with immense pride that Jodhpur has its own culture, quite distinct from, say, Jaipur or Jaisalmer. “Look at the clothes – we invented the jodhpuris,” he laughs. The main part of the town, housing an archaic clock tower, is fairly ordinary, except for the amount of colour on display. From the men’s turbans, which are blue, white or multi-coloured depending on what caste they hail from, to flowing ghaghras in shocking pink and electric green, there is colour everywhere. Living at the edge of desert, one would want this kind of palette to keep the eyes feasting on some life.

We make a beeline for Gypsy, a popular restaurant, for a Marwari thali. We’re served a wholesome meal – daal, baati, choorme ke ladoo, dhokla, rotis soaked in ghee, gattey ki sabzi, pooris andsaffron pulao – and coaxed into seconds by the owner, Mr. Chandali, who waits upon his guests in person, carrying out his cultural duty of ‘Manuhaar’ (hospitable persuasion) with elan. Replete with satisfaction, we head out to the next must-visit place in Jodhpur – the Mehrangarh fort.

The fort, situated on a hillock for strategic reasons, is a ramshackle giant of a site that is visible from anywhere in the city. It truly does look like the work of ‘angels, fairies and giants’, as Rudyard Kipling said way back in 1899. From its higher vantage point, one can see an ocean of blue houses winking up at us. Today, it wears a haunted look – threadbare, swept clean of life, unlike the living fort of Jaisalmer. It is perhaps this quality that led Christopher Nolan to feature the fort in The Dark Knight Rises as the backdrop for the prison-well in the middle of nowhere.

Within the fort, a few rooms are open to the public as a museum – on display here are accessories of the subject’s life, cultural investments that the kings endowed the kingdom with and religious strains. Miniature paintings between 1725 and 1843 that depict the transition from portraiture of the monarchs to sketching out abstract ideas of Vaishnavite religion find pride of place in the Diwan-e-Am (the court of the commoners). And we also spotted a more expensive-looking version of the afeem-making machine in a glass case here.

As the sun goes down, we ascend to new heights of magnificence. Strains of the sarangi, fused with sounds from the city below, waft in through exquisitely carved wooden doors and windows, cannons and other outdated armoury, and domes of all shapes and sizes, giving the evening a scintillating hue. We look upon the city milling about in the everyday, and are struck by the many contradictions that history has ordained this long-surviving nub of civilisation with.

Like Aldous Huxley once rather floridly stated: “From the bastions of the Jodhpur Fort one hears as the gods must hear from Olympus, the gods to whom each separate word uttered in the innumerably peopled world below, comes up distinct and individual to be recorded in the books of omniscience.” Perhaps this over-the-top description was also an inspired conjecture on some afeem-swilling night.